Digestive tract health is a key aspect of poultry maintenance. The digestive tract (gastrointestinal tract/GIT) consists of organs responsible for receiving food, digesting it, absorbing nutrients, and excreting waste, while also functioning as a lymphoid organ known as Gut Associated Lymphoid Tissue (GALT). (GALT). This plays a significant role in achieving optimal poultry performance. Along the small and large intestines, the digestive tract contains lymphoid tissues distributed within the epithelium and lamina propria, known as peyer’s patches and caecal tonsils. These form a local defense system that acts as the first line of response when pathogenic agents infect the digestive tract.

Digestive Tract Diseases

Digestive infections can damage the digestive tract, especially the intestinal mucosa, leading to nutrient absorption disorders. When this occurs, it can cause serious consequences such as poor growth, low uniformity, increased feed conversion ratio (FCR), and higher mortality rates. In broiler chickens, common digestive diseases include colibacillosis, coccidiosis, necrotic enteritis (NE), Newcastle disease (ND), and fowl cholera. In pre-laying layer chickens, frequent digestive issues include coccidiosis, colibacillosis, NE, cholera, ND, and helminthiasis. During the production period, digestive problems often found are helminthiasis, cholera, colibacillosis, NE, ND, avian influenza (AI), and mycotoxicosis. Digestive tract diseases are typically characterized by clinical symptoms such as diarrhea. In general, affected chickens appear lethargic with dull feathers.

Coccidiosis Infection

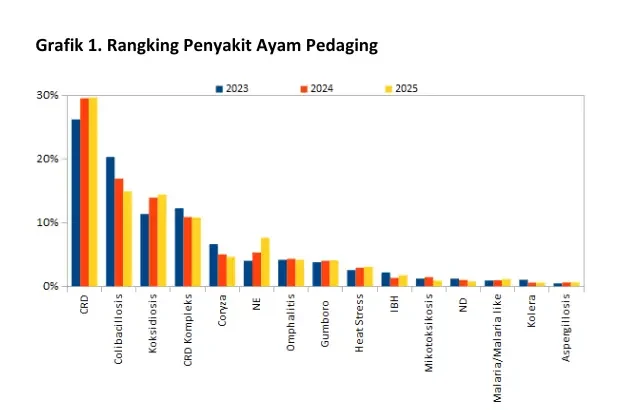

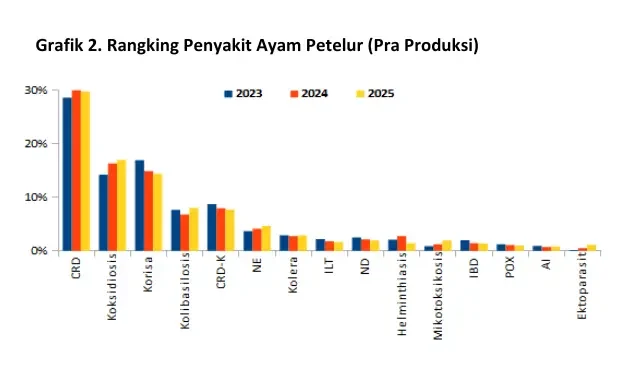

Based on data collected by Medion from 2023 to 2025, coccidiosis ranks as the third most common disease in broiler chickens and the second most common in pre-laying layer chickens (Figures 1 and 2). Coccidiosis is caused by the protozoan Eimeria spp., which attacks the digestive tract, particularly the small intestine and caeca. The species that cause disease in chickens include E. tenella, E. necatric, E. acervulina, E. maxima, E. brunetti, E. mitis, and E. Praecoc. Several factors can trigger the occurrence of coccidiosis, including high stocking density, excessive humidity in the poultry house, poor litter quality, a high level of oocyst contamination, and inadequate cleaning or downtime between flocks.

The impact of coccidiosis infection in chickens includes stunted growth, reduced feed efficiency, and mortality rates that can reach 80–90%. Coccidiosis also has an immunosuppressive effect, hindering the development of the immune system. It damages the intestinal mucosa, Payer’s patches and caecal tonsils is key immune organs within the digestive tract. Along the intestinal mucosa, lymphoid tissues produce antibodies (IgA) that help protect the gut lining from other diseases. Damage to the intestinal mucosa leads to a decrease in IgA production, thereby reducing the intestine’s ability to defend against secondary infections.

The clinical signs and anatomical changes caused by coccidiosis depend on the species of Eimeria involved. In general, chickens affected by coccidiosis show signs such as drowsiness, drooping wings, loss of appetite, and anemia. Infection with E. tenella causes bloody droppings, with feces appearing red or orange on the litter or beneath the cage. Infection with E. maxima results in thick, reddish feces mixed with small blood clots. Anatomical changes observed in E. tenella infections include enlargement of the caeca by two to three times, thickened and darkened intestinal walls, and the presence of blood clots in the caecal lumen. Meanwhile, infections by other Eimeria species cause intestinal wall thickening (which may be accompanied by inflammation, pus, or hemorrhage) and the appearance of white spots on the intestinal surface. Based solely on clinical signs and pathological anatomy, it is difficult to distinguish between Eimeria species, therefore, laboratory tests are needed for accurate identification.

Necrotic Enteritis Infection

Necrotic enteritis (NE) is caused by toxins produced by the bacteria Clostridium perfringens types A and C. NE infection in chickens leads to damage of the intestinal mucosa, impaired nutrient absorption, reduced growth, increased feed conversion ratio, depression, dull feathers, and even death. These effects ultimately result in decreased productivity. Several predisposing factors for NE include moist or wet litter, stress, and sudden weather changes. NE outbreaks can also be triggered by coccidiosis infections. Changes in intestinal content viscosity may further contribute to the onset of NE, often caused by feed with excessively high protein and energy content or sudden changes in feed formulation.

Chickens infected with this disease often show signs of diarrhea and wet litter. They may also be seen pecking at mucus-covered feces around the cloaca, commonly referred to as “Sticky Pings.” Infected birds tend to huddle together, appear drowsy, and have ruffled feathers. Due to damage to the mucosal lining, undigested feed particles such as corn residues are frequently found in the feces. Anatomical changes observed in necrotic enteritis (NE) cases include swollen intestines filled with gas, a distinct foul odor, and fragile intestinal walls that tear easily. In severe cases, the intestinal mucosa appears rough like a towel surface, a condition often called “Turkish Towel.”

Colibacillosis Infection

Colibacillosis is a disease caused by the bacterium Escherichia coli (E. coli), which belongs to the genus Escherichia and the family Enterobacteriaceae. Cases of Colibacillosis in chickens are generally caused by avian pathogenic E. coli (APEC) strains. So far, APEC has been dominated by three serotypes: O₁, O₂, and O₇₈. Colibacillosis can be transmitted through contaminated drinking water, litter, air, and feces.

The incidence of colibacillosis in both broiler and layer chickens remains among the top five poultry diseases, making it a condition that still requires close attention. Colibacillosis outbreaks on farms can occur as single infections, but mixed infections with other diseases are also common. The factors that trigger colibacillosis are closely related to poor management practices, such as high stocking density, accumulation of feces, and poor litter quality. Many colibacillosis outbreaks result from inadequate sanitation and hygiene in poultry houses and are directly linked to poor air and water quality on the farm.

Colibacillosis can occur in several forms, either as a local or systemic infection. The local forms of colibacillosis include omphalitis (navel inflammation) and yolk sac infection (yolk sac), cellulitis, which is characterized by yellowish-brown skin and the presence of thick pus-like exudate beneath the skin, and salpingitis, which causes inflammation of the oviduct or egg-laying tract, as well as localized colibacillosis infection in the form of diarrhea. The systemic form of colibacillosis occurs when E. coli bacteria enter the bloodstream, leading to colisepticemia. This infection can be observed through inflammation of the larynx, trachea, lungs, and cloudy air sacs, along with fibrinous membranes found on the heart (pericarditis), liver (perihepatitis), and abdominal cavity (peritonitis). This form of infection can also affect chicks aged 1–2 days, indicated by unabsorbed yolk sacs and enlarged spleens. After several days, characteristic lesions of serofibrinous polyserositis may develop, found on the peritoneum, pericardium, air sacs, and liver membranes.

Worm Infection

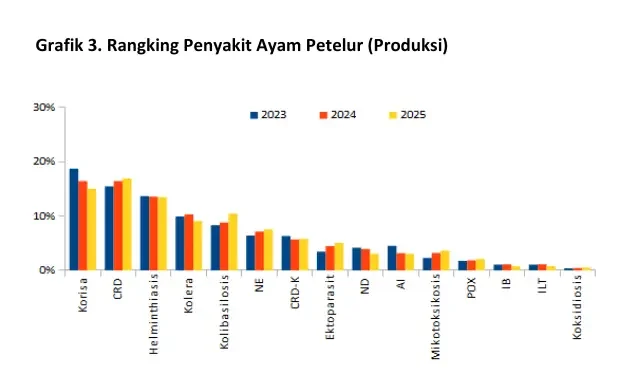

Over the past 3 years, worm infections have ranked 3rd among production-phase layer chickens (Figure 3) and remain in the top ten overall (Figure 2). This parasitic disease continues to threaten layer farms as long as management and biosecurity practices remain suboptimal, and the number of intermediate hosts or disease vectors such as flies continues to increase. The worms most commonly found infecting the digestive tract of layer chickens are roundworms (nematodes) such as Ascaridia galli and tapeworms (cestodes) such as Raillietina sp. In addition, there is another type of worm known as Acanthocephala. The Acanthocephala group belongs to the aschelminthes phylum and is neither classified as roundworms nor tapeworms (Panchani, 2021).

Chickens with mild worm infections may appear relatively healthy, although a decrease in egg production can occur. In severe infections, chickens show signs such as reduced appetite, stunted growth, emaciation, rough feathers, paleness, significant drop in production, and diarrhea, with worms sometimes visible in the feces. During necropsy, worms can be found in the intestines. Severe infestations—particularly those caused by tapeworms or Acanthocephala, often result in enteritis (inflammation of the intestines), characterized by thickening of the intestinal wall, the presence of nodules, and intestinal haemorrhage (bleeding).

Controlling Digestive Tract Diseases

The intestinal length and large diameter are followed by well-developed villi and crypts, resulting in a more optimal absorption area. With good feed digestibility and nutrient absorption, the feed conversion ratio (FCR) will improve, helping to reduce mortality rates. Several factors influence the quality of digestive organs, including:

1. Early Rearing Management

The quality of the digestive organs is influenced from the very beginning of rearing, starting with the immediate provision of feed upon chick arrival and the implementation of proper brooding management. This can be observed in the development of the digestive organs. For example, the intestines of two-day-old chicks that received feed immediately after placement are longer and larger compared to those that were fasted for eight hours or not given feed at all.

2.Risk of Disease Agent Exposure

Good biosecurity practices help minimize the presence of disease-causing agents in the poultry house area. This significantly reduces the risk of chickens becoming infected with digestive tract diseases.

3. Condition of Intestinal Microflora

It is important to maintain a balanced intestinal microflora to prevent excessive growth of pathogenic bacteria.

4. Feed Quality

Feed contaminated with fungal toxins (mycotoxins) can damage digestive organs such as the intestines, gizzard, and liver. It is also important to pay attention to the presence of antinutritional substances in feed, such as phytic acid and NSPs (non-starch polysaccharides). Maintaining a balanced intestinal microflora is essential to prevent excessive growth of pathogenic bacteria.

To control digestive diseases, it is necessary to combine good biosecurity implementation, proper poultry management practices, and the provision of feed that meets the animals’ nutritional needs in both quality and quantity.

- DOC selection before placement in the house is important, especially to identify those showing symptoms of colibacillosis such as a wet navel. If such chicks are kept, their productivity will not be optimal and they may spread the infection to other poultrys.

- Implementing good biosecurity practices includes routinely sanitizing the poultry house, both during downtime and while it is occupied. This involves applying the three-zone biosecurity system, restricting visitors and other animals from entering the farm area, and spraying vehicles with disinfectants such as Medisep and Zaldes before entering or leaving the premises. Additionally, dipping and spraying footwear before entering the poultry house using Antisep, as well as cleaning and disinfecting equipment and the poultry environment with Medisep or Neo Antisep, are crucial steps in maintaining biosecurity.

- Pay attention to stocking density and ensure proper air circulation within the poultry house. Clean dust around the housing area, as it may be contaminated with disease-causing agents. Good ventilation should be maintained to allow easy air exchange and to keep the chickens comfortable.

- Administer deworming medication regularly. Dewormers should be given even before any signs of worm infestation appear. For layer chickens raised in floor (postal) housing during the pullet phase, deworming should be carried out at one month of age and repeated one to two months later. For pullet chickens kept in battery cages, deworming should be administered when they are moved to the production cages and repeated every 3-4 months.

- Minimize the fly population around the poultry house by using Larvatox to eliminate fly larvae and Flytox to control adult flies.

- Regularly monitor water quality, especially during seasonal changes and when constructing new wells.

- Implement good litter management practices. Regularly turn over the litter. If clumps are found, separate and remove them. When large amounts of wet or compacted litter are observed, cover the area with fresh litter.

- Pay attention to feed storage in the warehouse. Use pallets or flooring, ensure proper air circulation, and arrange feed stacks appropriately.

- If a digestive tract infection occurs, the following actions can be taken:

- Isolate chickens that are severely ill or showing clinical symptoms.

- In cases of colibacillosis or necrotic enteritis (NE) infections, antibiotics can be administered through drinking water, such as Tinolin or Neo Meditril. However, if the chickens are severely affected and their water intake decreases, treatment can be considered using injectable antibiotics such as Tinolin Injection, Neo Meditril, or Lincomed. During treatment, several factors must be considered, not only the correct dosage and duration of administration, but also the rotation of antibiotics from different classes to prevent antibiotic resistance

- For coccidiosis infection, administer Therapy or the herbal product Fithera for treatment.

- For worm infection treatment, deworming can be carried out using Levamid, which is effective against tapeworms (Raillietina sp.) and roundworms (Ascaridia sp.) in both larval and adult forms. To control worm infections caused by Acanthocephala, administer Levamid at a dosage of 0.2 g/kg body weight or Wormzol-K at 0.1 g/kg body weight through feed for three consecutive days, which can be repeated two weeks later until the infection is completely resolved, or every one to two months depending on the severity. Wormisol may also be used, administered through drinking water without medication after fasting the chickens for 1–2 hours before treatment. After administering the dewormer, continue with regular drinking water or Gingertol at 2 ml/L to help increase the chickens’ water intake.

- Improve management practices by removing feces or litter contaminated with blood, adjusting bird density, opening and closing curtains as needed, and replacing any damp litter.

- Administer multivitamins such as Vita Stress or Fortevit after the treatment is completed.

- Lakukan sanitasi serta desinfeksi peralatan dan air minum (Desinsep) jika sumber air positif tercemar E. Coli infection serta bakteri lain.

- Disinfect the poultry house using Medisep or Neo Antisep.

- Provide supportive therapy to help control and improve the permeability of the digestive tract.

- Regularly stir or rotate the feed to help stimulate the chickens’ appetite.

- Provide premix supplements to help improve the digestive process, such as Betterzym.