Infectious Laryngotracheitis (ILT) is one of the major diseases frequently affecting chickens. This disease, caused by the Gallid herpesvirus type 1 (GaHV-1) [1], continues to pose significant challenges, particularly in the upper respiratory system of poultry. As its name suggests, Laryngotracheitis refers to inflammation primarily occurring in the larynx and trachea organs.

Current Situation of ILT

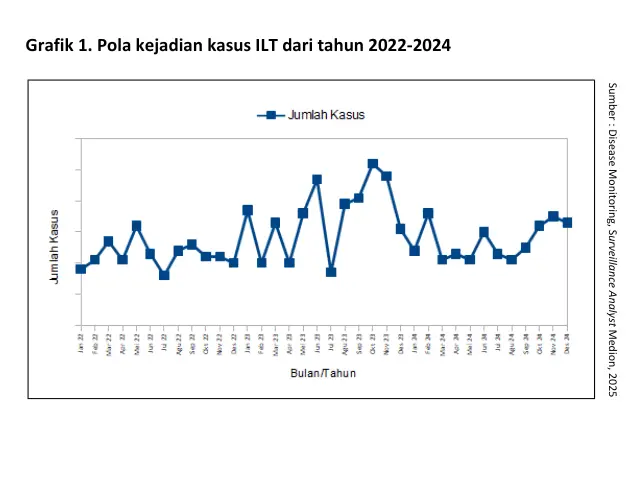

What is the current situation of ILT disease spread in Indonesia? Based on data collected by the Surveillance Analyst team from Medion over the past three years (2022–2024), there have been 1,017 suspected ILT cases identified through clinical symptoms and anatomical pathology findings during necropsy (chicken dissection). For the 2025 update, from January to April, 98 suspected ILT cases have already been reported.

The pattern of ILT case occurrences observed throughout last year showed an increasing trend toward the end of the second semester of 2024 (Figure 1). It is known that September to December marks the rainy season in Indonesia. This rising trend in ILT cases should be closely monitored, especially considering the predicted “wet dry season” in 2025. This information was reported on May 28, 2025, through the official website of the Meteorology, Climatology, and Geophysics Agency (BMKG).

What exactly is the “wet dry season” phenomenon?

Recently, unpredictable weather patterns have made the term “wet dry season” more common. This phenomenon occurs when rainfall continues during periods that should already be part of the dry season. Such weather anomalies are often linked to global warming. The BMKG predicts that several regions in Indonesia will experience a wet dry season in mid-2025. This condition is influenced by global factors such as the movement of La Niña. La Niña itself is a cooling phenomenon of sea surface temperatures in the central Pacific Ocean, which can increase rainfall in Indonesia, especially in areas with warm waters. As a result, the dry season this year is expected to arrive normally or slightly later in some regions of Indonesia, with overall rainfall levels remaining within the normal category [2].

The BMKG stated that this wet dry season phenomenon is expected to last until August 2025, followed by a transitional period (pancaroba) from September to November, and the rainy season from December 2025 to February 2026 [2]. From a livestock management perspective, such weather conditions can have significant impacts. Disease-causing agents tend to thrive in humid environments. When chickens experience decreased immunity (immunosuppression), pathogens can more easily infect them—one of which is ILT.

According to data from Medion’s Surveillance Analyst team, cases of ILT disease in Indonesia have spread almost evenly across the country. The highest incidence rates from 2022–2024 were recorded in South Sulawesi, as indicated by the red areas on the distribution map shown in Figure 1. The red color represents a high case prevalence in that province (>40% of national suspected cases). Meanwhile, several other regions such as West Sumatra, South Sumatra, and East Java also showed relatively high numbers of suspected ILT cases (green areas) with a prevalence of more than 5% of national suspected cases. In contrast, other regions marked in blue on the map indicate a case prevalence of less than 5% of national suspected cases.

Economic Losses

ILT causes economic losses primarily due to increased morbidity (50–70%), moderate mortality (10–20%) [3], reduced daily weight gain, decreased egg production, and additional costs for vaccination, biosecurity measures, and treatments to combat secondary infections from other poultry diseases [4]. In the field, ILT infections are often found alongside other pathogenic agents such as Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and Mycoplasma gallisepticum [3]. Coinfections with other respiratory pathogens and poor environmental conditions can severely affect the respiratory system and prolong the course of the ILT disease [4].

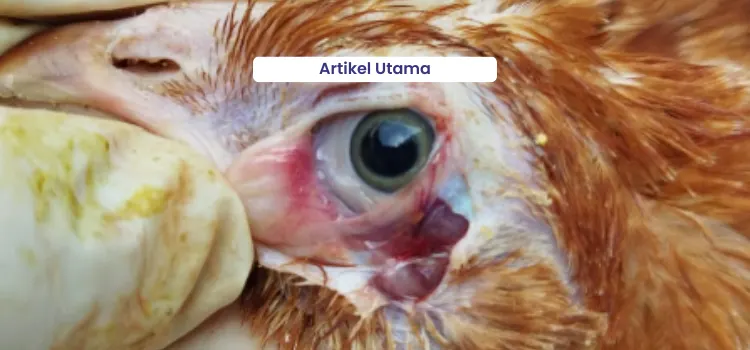

In chickens, ILT manifests in three primary forms: peracute, acute or epizootic (severe), and chronic or mild [9]. Generally, the peracute and acute forms are characterized by severe respiratory distress, sneezing, discharge of mucus mixed with blood, severe tracheitis, and conjunctivitis (inflammation of the eye’s conjunctival membrane), accompanied by a relatively high mortality rate (up to 70%). The milder chronic form (mild) is indicated by mild to moderate catarrhal tracheitis (Figure 5), sinusitis, and conjunctivitis, with relatively low morbidity and light mortality, usually less than 2% [4]. However, the precise estimation of economic losses caused by this disease remains uncertain [1].

ILT Causative Agent and Host

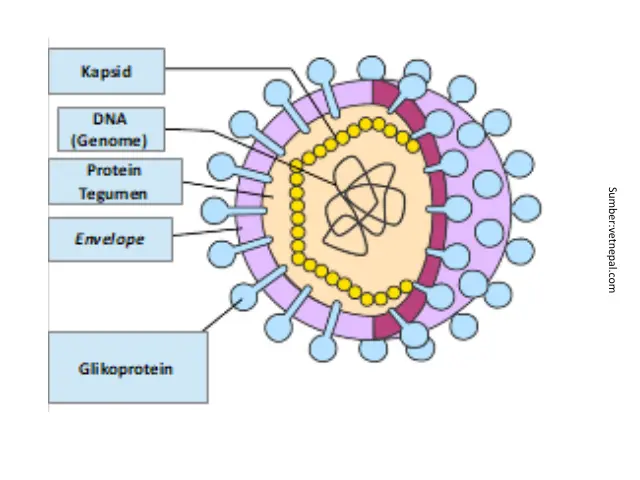

ILT is caused by infection with the Gallid herpesvirus 1 (GaHV-1), which belongs to the genus Iltovirus, subfamily Alphaherpesvirinae, and family Herpesviridae [5]. The ILT virus contains double-stranded DNA as its genetic material, featuring a nucleocapsid [6] approximately 100 nm in diameter, with the complete viral particle measuring about 200–350 nm [7]. The nucleocapsid has an icosahedral symmetry surrounded by a protein tegument layer and is encapsulated by an outer envelope composed of virus-encoded glycoproteins (Figure 2) [1].

Chickens are the primary host and main target of Gallid herpesvirus 1 (GaHV-1) infection [4]. However, researchers have observed that the natural host range of the virus can also include other species within the order Galliformes, such as ornamental fowl (pheasants), crossbreeds between chickens and ornamental fowl, peafowl, and turkeys. In contrast, other birds within the Galliformes order—such as starlings, sparrows, crows, pigeons, ducks, and guinea fowls—are relatively resistant to GaHV-1 infection [1]. To date, there have been no reported cases of transmission or infection of this virus from poultry to humans [9].

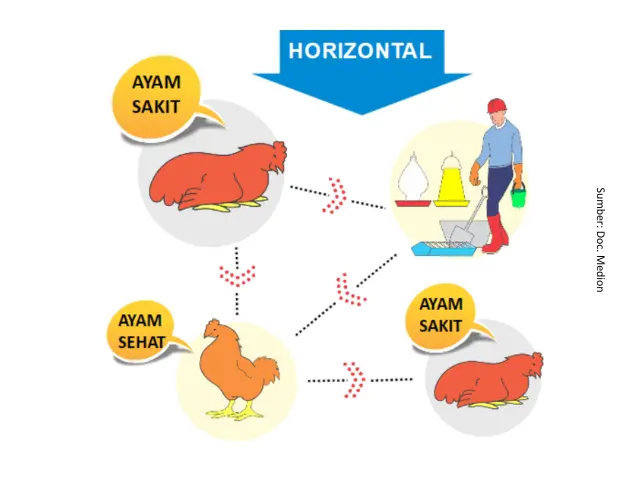

The Infectious Laryngotracheitis (ILT) virus enters a chicken’s body through the respiratory and ocular routes. It begins replicating once it reaches the epithelial cells of the conjunctiva, respiratory sinuses, larynx, and the upper respiratory tract more broadly [10]. Transmission of ILT occurs both directly and indirectly (Figure 3). Infected chickens can shed the virus through respiratory secretions, directly infecting other chickens or indirectly contaminating equipment, litter, feeders, vehicles, dust, footwear, clothing, or visitors carrying the virus. Contact with these contaminated sources can lead to ILT infection in other chickens [4].

Like other herpesviruses, the ILT virus can persist in the central nervous system, specifically in the trigeminal ganglion, and enter a latent state approximately seven days after the acute phase of infection. Chickens that have been infected with the ILT virus can become carriers. These carrier chickens, having survived previous infections, can act as sources of infection for uninfected birds. Although direct transmission from chicken to chicken occurs more frequently than infections caused by contact with chickens in the latent or carrier phase, chickens actively infected with ILT are far more contagious, shedding the virus through oral secretions more readily than clinically recovered or carrier birds [4]. On some farms, beetles and litter-dwelling larvae have also been reported as potential transmission vectors. Studies have found live ILT virus in beetles up to 42 days after an outbreak occurred on the farm [11].

Clinical Symptoms and Pathological Changes

The incubation period of ILT varies between 6–14 days. The clinical duration of the disease ranges from 11 days to 6 weeks, depending on the severity of the infection. The severity is influenced by factors such as viral virulence, stress conditions, presence of coinfections with other pathogens, flock immunity status, and the age of the chickens. ILT infection in chickens can manifest in three forms: peracute, acute, and chronic [4].

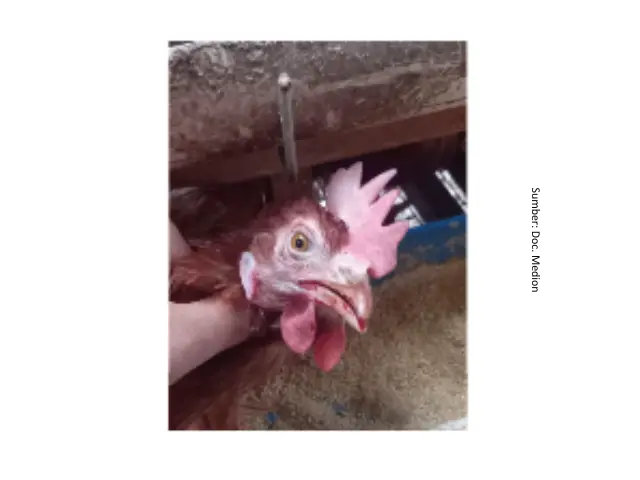

The peracute form of infection occurs suddenly, spreading rapidly and resulting in a high mortality rate of up to 50% [12]. Affected chickens show signs of weakness (lethargy), moderate to severe conjunctivitis (Figure 4) accompanied by swollen eyelids and increased tear production (Figure 5). In some cases, sudden death may occur without prior visible clinical symptoms [1]. This peracute form is characterized by clinical signs such as difficulty breathing (dyspnea) and gasping, where chickens extend their heads and necks while breathing. Coughing also occurs as the birds attempt to expel blood clots obstructing the trachea (Figure 7) [13]. These expelled clots (Figure 8) are often found on the floor and walls of the coop [9]. Chickens infected with the peracute form typically die within three days [4].

The acute form of ILT shows clinical signs of respiratory distress such as dyspnea, but with less severity compared to the peracute form. Affected chickens tend to be weak, inactive, and exhibit reduced appetite [10]. Pathological changes are similar to those in the peracute form, including obstructions in the trachea caused by blood clots that make breathing difficult and cause birds to open their mouths while inhaling. Yellow, cheese-like masses (caseous exudates) may also be observed in the primary bronchi when lesions spread deeper into the respiratory tract [12]. The acute form of ILT can cause mortality rates ranging from 10% to 30%, with morbidity reaching up to 100% for approximately 15 days. In laying hens, production drops vary in severity but typically recover after a certain period [14].

The chronic form of ILT is milder compared to the acute or peracute forms. It exhibits clinical symptoms similar to other respiratory infections, such as stunted growth, coughing, mucus discharge, head shaking, squinting or partially closed eyes, and swelling of the infraorbital sinus. In chronic ILT cases, a decrease in egg production of up to 10% has been reported, with low mortality rates (<2%) and morbidity rates reaching around 5% [14].

Disease Diagnosis

In diagnosing ILT, the acute form can be identified based on case history, clinical symptoms, and the presence of characteristic (pathognomonic) anatomical pathology lesions. The mild form of ILT is often mistaken for other respiratory diseases; therefore, laboratory confirmation is necessary [18]. Further diagnosis can be performed using laboratory tests aimed at detecting the causative agent or identifying the immune response (antibody) produced. To confirm clinical cases, diagnostic tests can be used to detect the presence of ILT virus in tissue samples or tracheal exudates. Methods include virus isolation, immunofluorescence, ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay), and PCR (polymerase chain reaction). To detect ILT-specific antibodies through serological testing, ELISA or VN (virus neutralization) methods can be applied [9]. Differential diagnoses for diseases resembling ILT include the diphtheritic (wet) form of fowl pox and infectious coryza [18].

ILT Control Strategies

1. Treatment

Treatment with antibiotics or antibacterial agents during an outbreak can be administered when secondary bacterial infections occur [18]. To alleviate respiratory symptoms, natural remedies such as Respitoran can be given, as it acts as a decongestant. Respitoran contains extracts of Tussilago and Thyme to help relieve respiratory disorders in chickens caused by infections such as ILT.

2. Implementation of Biosecurity and Farm Management

Biosecurity serves as the first line of defense in preventing the entry of ILT virus into poultry farms. Restrictions on human and vehicle movement, as well as routine disinfection of equipment and facilities, must be implemented with strict discipline. Because the ILT virus is an enveloped virus, it can be easily destroyed using various types of disinfectants. During the production period or in the event of an outbreak, oxidizing agent-based disinfectants containing Povidone iodine, such as Neo Antisep New Formula, or QUAT-based disinfectants containing Benzalkonium chloride, such as Zaldes, can be used effectively.

In the event of an outbreak, litter and organic materials such as feces must be completely removed or cleaned from the coop after the production period ends. Subsequently, thorough cleaning, sanitation, and disinfection should be carried out. It is also recommended to leave the coop empty for at least 14 days before introducing a new flock to ensure that the environment is free from pathogenic agents.

3. Vaccination Strategy

ILT Under Control, Minimum Reaction, Optimum Protection

Vaccination is one of the key components in ILT control. It is recommended to vaccinate using Medivac ILT LS 2–3 weeks before the age at which ILT cases are most likely to occur, or according to general guidelines as shown in Table 1. Medivac ILT LS is an ILT vaccine containing live attenuated Infectious Laryngotracheitis (ILT) virus of the A 96 strain, produced using CEO (chicken embryo origin) technology. This vaccine can be used in broilers, male chickens, layers, and breeders, with a dosage of one dose per bird administered via eye drops.

When vaccinating against ILT using the live vaccine Medivac ILT LS, an important consideration is that ILT vaccination should not be performed close to the administration of live ND or IB vaccines. Studies have shown that when ILT and live ND vaccines are given simultaneously or within a short interval to young chickens, there is a significant decrease in the immune response to ILT. This immunosuppressive effect occurs when the ILT vaccine is administered within the period from 3 days before to 5 days after vaccination with the live ND vaccine in chickens under 5 weeks of age. However, this effect is not observed in chickens older than 7 weeks. These findings highlight the need for special attention when scheduling live ILT and ND vaccinations close together or when vaccinating young birds [15].

Although research has shown that administering the ILT vaccine together with the live IB vaccine via eye drops does not cause adverse interactions [15], it is still advisable to evaluate the vaccination results afterward. To reduce possible post-vaccination reactions, supportive therapy using the herbal product Respitoran can be given.

4. Immune and Environmental Support

The immune response to ILT primarily relies on the cell-mediated immune (CMI) system rather than the humoral response [17]. Therefore, maintaining the health of chickens through the administration of multivitamins and antioxidants (such as vitamins C and E), like Vitesel-C, as well as ensuring proper environmental hygiene (reducing dust and ammonia), are crucial to minimizing ILT predisposing factors in poultry houses. The use of immunostimulant or herbal supplements such as Imustim can also support the immune system, but must be complemented by strict management and biosecurity practices.

Controlling ILT in laying hens requires synergy between strict biosecurity, proper vaccination management, early detection, accurate diagnosis, and comprehensive poultry health management.

References

- Garcia, M & Spatz, S, 2020. Infectious Laryngotracheitis. Dalam Swayne, S. Disease of Poultry 14th Edition. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Hal 189-209

- https://gaw-bariri.bmkg.go.id/index.php/karya-tulis-dan-artikel/artikel/265-musim-kemarau-basah-fenomena-penyebab-dan-dampaknya-di-indonesia. Diakses pada 24 Juni 2025.

- Dinev, I. 2007. Disease of Poultry A Colour Atras. CEVA SANTE ANIMAL 1st Edition.

- Gowthaman V, Kumar S, Koul M, Dave U, Murthy TRGK, Munuswamy P, Tiwari R, Karthik K, Dhama K, Michalak I, Joshi SK. Infectious laryngotracheitis: Etiology, epidemiology, pathobiology, and advances in diagnosis and control – a comprehensive review. Vet Q. 2020 Dec;40(1):140-161. doi: 10.1080/01652176.2020.1759845. PMID: 32315579; PMCID: PMC7241549.

- Davison AJ, Eberle R, Ehlers B, Hayward GS, McGeoch DJ, Minson AC, Pellett PE, Roizman B, Studdert MJ, Thiry E.. 2009. The order Herpesvirales. Arch Virol. 154(1):171–177

- Roizman B, Pellett PE.. 2001. The family Herpesviridae: a brief introduction. In: Knipe M, Howley PM, editors. Fields virology. 4th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott Williams Wilkins; pp. 2381–2397

- Granzow H, Klupp BG, Fuchs W, Veits J, Osterrieder N, Mettenleiter TC.. 2001. Egress of alphaherpesviruses: comparative ultrastructural study. J Virol. 75(8):3675–3684

- https://vetnepal.com/article_details/Infectious-Laryngotracheitis-in-poultry . Diakses pada 24 Juni 2025

- WOAH Terrestrial Manual 2021. Chapter 3.3.3. – Avian infectious laryngotracheitis.

- Guy JS, Bagust T.. 2003. Laryngotracheitis. In: Saif M, Barnes HJ, Glisson JR, Fadly AM, McDougald LR, Swayne D, editors. Diseases of Poultry 11th edition. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press; p. 121–134

- Ou S, Giambrone J, Macklin K.. 2011. Infectious laryngotracheitis vaccine virus detection in water lines and effectiveness of sanitizers for inactivating the virus. J Appl Poult Res. 20(2):223–230

- OIE . 2014. Avian infectious laryngotracheitis. Man Diagn Tests Vaccines Terr Anim. Chapter 2.3.3.

- Blakey J, Stoute S, Crossley B, Mete A.. 2019. Retrospective analysis of infectious laryngotracheitis in backyard chicken flocks in California, 2007-2017, and determination of strain origin by partial ICP4 sequencing. J VET Diagn Invest. 31(3):350–358.

- Creelan JL, Calvert VM, Graham DA, McCullough SJ.. 2006. Rapid detection and characterization from field cases of infectious laryngotracheitis virus by real-time polymerase chain reaction and restriction fragment length polymorphism. Avian Pathol. 35(2):173–179

- Vagnozzi A, García M, Riblet SM, Zavala G. Protection induced by infectious laryngotracheitis virus vaccines alone and combined with Newcastle disease virus and/or infectious bronchitis virus vaccines. Avian Dis. 2010 Dec;54(4):1210-9. doi: 10.1637/9362-040710-Reg.1. PMID: 21313841.

- Toshiro IZUCHI, Takeshi MIYAMOTO, Influence of Newcastle Disease and Infectious Bronchitis Live Virus Vaccines on Immune Response against Infectious Laryngotracheitis Live Virus Vaccine in Chickens, The Japanese Journal of Veterinary Science, 1984, Volume 46, Issue 4, Pages 533-539, Released on J-STAGE February 13, 2008, Online ISSN 1881-1442, Print ISSN 0021-5295, https://doi.org/10.1292/jvms1939.46.533

- Ou SC, Giambrone JJ. Infectious laryngotracheitis virus in chickens. World J Virol. 2012 Oct 12;1(5):142-9. doi: 10.5501/wjv.v1.i5.142. PMID: 24175219; PMCID: PMC3782274.

- Tabbu, 2000. Penyakit Ayam dan Penanggulanannya : Penyakit Bakterial, Mikal, dan Viral. Yogyakarta : Kanisius